Assessment in the Professional Experience Context

Natalie Brown

Centre for the Advancement of Learning and Teaching University of Tasmania

Natalie.Brown@utas.edu.au

Abstract

Professional Experience is a key component of teacher education programs, bringing together the different disciplines of Education into a real-world setting. Helping pre-service teachers see theory in practice and begin to put theory into practice requires a close and explicit linkage between the coursework and practicum. A shared discourse that is accessible to pre-service teachers, field-based colleague teachers and university lecturers is an essential element in this process, particularly as there is an embedded assessment component. This project describes the evaluation of an assessment rubric developed for Professional Experience in the Bachelor of Teaching at UTAS.

Introduction

Preparation of professionals through degree and post-graduate programs has become an important role of Australian tertiary institutions. This provides a significant challenge for universities requiring engagement with professional practice (Boud, 1999) and explicit connection of university coursework with experiences in the field setting (Arnold, Loan Clark, Harrington & Hart, 1999). The use of supervised professional work placements, therefore, can have an important role in professional preparation, allowing socialisation into the profession, an opportunity to learn in context from first hand experience, (Lizzio & Watson, 2004) and to develop ability to reflect on practice (Schön, 1983).

Capitalising on the potential of work placements goes beyond the placements themselves requiring a systematic integration of theory and practice (Brown & Shipway, 2006). Achievement of this is not straightforward. Thomson (2000, p.70), writing of teacher education, states the 'Theory (University) and Practical (School) binary works to render relatively invisible their similar concerns, shared beliefs and sociological practices'. Consequently, this 'boundary struggle' can affect the exchange of ideas. This milieu is not ideal for the novice professional battling with the existential demands of either the workplace or university coursework. Clearly, an integrated and collaborative approach between universities and work placement providers is essential.

In Australia, teacher preparation has recently come under the scrutiny of an Australian Government House of Representatives inquiry (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education & Vocational Training [HRSCE&VT] 2007). This has followed questioning of whether current teacher education programs are producing graduates who are adequately prepared to meet both the changing demands of a complex profession as well as the reality of practice (Eyers 2005). Unsurprisingly, the Government report found that "High quality placements for school-based professional experience are a critical component of teacher education courses" and "beginning teachers consistently rate practicum as the most useful part of teacher education courses" (HRSCE&VT 2007, p. 67) in preparing them as teachers.

The importance placed on the practicum by the Government inquiry is also reflected in the 12 key recommendations, a number having reference to the practicum. That university staff "maintain close links with students" (HRSCE&VT 2007, p.77) and "provide ongoing support to supervising teachers throughout the practicum period" (HRSCE&VT 2007, p. 78) reflects an emphasis on involvement in the practicum by university staff. Clarification of expectations was also singled out with the university needing to "make clear to teachers what is expected of them as practicum supervisors" (HRSCE&VT 2007, p.78), especially in the area of assessing the pre-service teacher.

The findings of the Government report synergise well with initiatives that have been undertaken at the University of Tasmania (UTAS). In recognition of the importance of Professional Experience, the major employers of teachers in Tasmania (Tasmanian Government Department of Education, Catholic Education Office and Association of Independent Schools of Tasmania) joined with Education Faculty staff to form the Partners in Professional Practice Working Group (PPWG) in 2005. An early focus of the PPWG was to identify issues and problems related to Professional Experience at UTAS. In summary, the group found that communication, liaison, role clarity, course requirements, connections between theory and practice, and assessment of pre-service teacher competence continued to be problematic (Brown & Shipway, 2006).

As a result of this PPWG alliance, a series of principles that would underpin future collaborations were agreed upon and a number of initiatives proposed for trial. Parallel to this collaboration, work began in the post-graduate Bachelor of Teaching program (B.Tch) on an assessment rubric with an aim to provide a common framework and shared language for mapping pre-service teachers' progress across their two year degree. This was also seen as a priority to support the embedded assessment component of the practicum, primarily carried out by colleague teachers (with support from university supervisors). This work also had the potential to address many of the issues that had been identified by the PPWG.

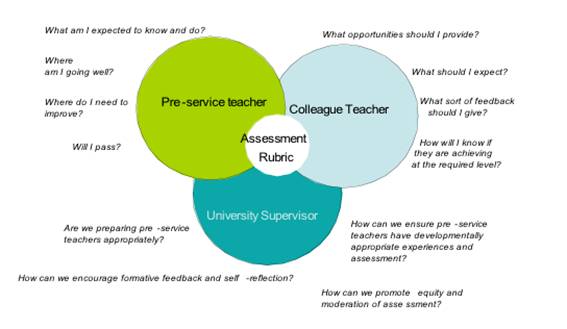

Development of shared understanding of expectations and clarity of goals has commonly been identified as an important element in a successful practicum (Connor & Killmer, 1995; Haigh & Tuck, 1999; Darling-Hammond & Baratz-Snowden, 2005). This is also important from the perspective of increasing pre-service teacher agency, in a situation where they are being assessed (Ortlipp, 2003; Turnbull, 2003). Arriving at this shared understanding between stakeholders requires interrogation of the perspectives of each - pre-service teachers, colleague teachers and university supervisors (Figure 1).

The assessment rubric was developed by the author in 2005 (a detailed description of the development is provided in Brown, 2006). Using explicit indicators, the rubric attempts to provide a shared discourse accessible to pre-service teachers, colleague teachers and university supervisors (Brown, 2007). Five criteria, based on the National Beginning Teacher Competencies (Australian Teaching Council, 1996), were used as a framework due to their wide recognition by colleague teachers. The rubric also drew on other frameworks in the developmental stage (NSW Institute of Teachers, 2005; Department of Education, Tasmania, 2005.) Unpacking each of the five criteria to articulate indicators that would be expected in each of the four Professional Experiences 1 was taken as a starting point. The rubric was also designed to make explicit the goals for sophisticated practice incorporating a fifth (or aspirational) level.

Figure 1: Professional Experience: Towards a shared understanding

Concurrently with the development of this rubric at UTAS, a team of teacher educators at the Hong Kong institute of Education were working on a similar project. They were developing a progress map for initial teacher education that could be similarly used as a standards referenced assessment instrument for field experience (Tang, Cheng & So, 2006). Following a similar process, this group drew, from the literature, exemplars of professional standards from other countries and contextualised these for their own programs. Using only three dimensions, 'professional attributes', 'teaching and learning' and 'involvement in education community', the Hong Kong team mapped these over four levels of professional development to illustrate the "continuum of growing professional competence" (Tang, Cheng & So, 2006, p. 226).

The UTAS 'Professional Experience Assessment Rubric' was introduced to the program in 2006 following a small pilot study in late 2005. In 2006, amendments were made and the resulting rubric further reviewed by the B.Tch staff as a result of feedback from colleague teachers, pre-service teachers and academic staff during the pilot. This review considered the cohesiveness of learning outcomes between the assessment rubric and the coursework components of the degree. As a result of this work, some alteration to sequencing of course content was made to better align with expected outcomes for each successive practicum as expressed on the rubric.

This paper reports on a field-based evaluation of the rubric as an assessment tool for Professional Experience.

Methodology

The evaluation of the assessment rubric occurred as a component of a broader research project conducted during B.Tch Professional Experience 3 in Semester 1, 2007. The focus of the larger project was developing a closer partnership between schools and the Faculty of Education. The following research question was posed in connection with assessment:

How effective is the Assessment Rubric (Brown, 2006) for formative and summative assessment of pre-service teachers during practicum and does it need refinement?

Selection of schools:

The study was conducted in a cluster of 12 metropolitan schools, geographically contiguous and encompassing both government and non-government schools. The cluster was purposefully chosen due to the schools having accepted a large number of pre-service teachers (30) for Professional Experience 3. Its proximity to the University (for ease of access by the researchers) was also taken into account. The participating schools comprised of two infant, four primary, one secondary, two senior secondary, one K-10 and two K-12 schools. Of these, eight were government schools and four were from the non-government sector.

Participation of Teachers:

The project involved approximately 40 colleague teachers in addition to a small number of Professional Experience coordinators in schools. Prior to commencement of the practicum, all principals and coordinators received information letters with respect to this project. Colleague teachers received an information pack, including the assessment rubric, from their pre-service teacher on or before the first day of practicum.

All colleague teachers and Professional Experience coordinators were invited to attend an induction and feedback session with the university supervisors. These sessions were held at a local school, after school hours allowing for travel time. As an incentive for teachers to attend, afternoon tea was provided together with an offer of a one-off payment ($50) to schools for each teacher who attended both sessions. The induction session covered information on the expectations of the practicum and guidance on the use of the assessment rubric. There was also time given for colleague teachers to raise issues about this and previous practicum experiences. The feedback session allowed colleague teachers to discuss issues that arose during the current practicum and to offer suggestions for improvements.

Participation of University Staff:

Two University staff participated in the project in multiple roles as researchers, facilitators of the induction, feedback and pre-service teacher workshops and as university supervisors for all of the pre-service teachers assigned to the cluster. With respect to visits to pre-service teachers, one staff member visited 15 pre-service teachers in six schools and the second (the author) visited 16 pre-service teachers in seven schools (one pre-service teacher was visited by both supervisors).

Data collection and analysis

As this research set out to investigate a real world issue, broadly to enhance Professional Experience and, specifically, to investigate assessment, a pragmatic underpinning has been applied to the methodology (Creswell, 2003). Consistent with this approach, multiple sources of data, both qualitative and quantitative, have been collected. There were four main data sources:

- Questions and comments raised by colleague teachers at the induction and feedback sessions as recorded by a research assistant.

- A post-practicum survey completed by colleague teachers that included questions related to assessment and the rubric.

- A post-practicum survey completed by pre-service teachers that included questions related to assessment and the rubric.

- University supervisors' records of visits to schools and discussions with colleague teachers.

Quantitative data was collected through placement records (numbers of schools, colleague teachers and pre-service teachers) and through Likert scale responses to questions posed on the post-practicum surveys. Due to the small numbers of participants, no detailed statistical analyses have been performed with quantitative data used for descriptive purposes and to clarify and situate the qualitative data.

Qualitative data was collected through colleague teachers' comments and questions, university supervisors' records as well as open response questions on the post-practicum surveys. This data was analysed through a process of reading through and becoming familiar with the responses followed by a collation and categorisation process in order to address the research question (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Patton, 1990).

The two sources of data collected from colleague teachers, comments from the induction and feedback, together with the survey were analysed together. The pre-service teacher data was wholly obtained from the survey. The data collected by university supervisors was used to triangulate data from both colleague teachers and pre-service teachers.

Results and Discussion

Colleague Teacher Evaluation of the Rubric

Despite the incentives offered to teachers to attend the induction session, only a small number (6) attended, representing less than 20% of teachers who were involved in the practicum. Two of the attendees had not previously hosted a pre-service teacher. The teachers who attended appreciated the opportunity to raise questions and to be seen as important partners in Professional Experience. With the respect to the rubric, all teachers at the induction session commented on it being able to clarify expectations. They anticipated that they would use it when planning experiences for their pre-service teachers and in giving feedback. One colleague teacher (who had worked with pre-service teachers from a number of pre-service courses) commented that 'it would be good if all programs used a similar system'.

Evaluation of the rubric after the practicum was carried out through survey and interview at the feedback session. In all, eleven colleague teachers contributed to the feedback with results summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Colleague teachers' responses feedback on the assessment rubric

| Question | Yes |

No |

No response |

|---|---|---|---|

Were you aware of the rubric? |

92% (11) |

8% (1) |

|

Was the rubric useful during the practicum? |

92% (11) |

8% (1) |

|

Were the indicators appropriate for this practicum? |

100% (12) |

|

|

Do the indicators in the rubric require alterations or additions? |

8% (1) |

92% (11) |

|

Do you think it would be possible for pre-service teachers to reach the next level of the rubric on the subsequent practicum? |

92% (11) |

|

8% (1) |

Overwhelmingly, the responding colleague teachers considered the rubric a valuable tool for assessing pre-service teachers. All except one indicated that they had used the rubric and this teacher intimated it was because they "didn't know about the rubric" but, after having seen it, thought that it would have been very useful. The only teacher who found the rubric not useful was in the Languages other than English (LOTE) area. This teacher found that the indicators were not specific enough for this subject area and believed it did not give her a great deal of guidance on setting expectations.

The majority of colleague teachers responding to the survey reported using the rubric for both formative and summative assessment. The formative assessment was delivered predominantly through post-observation discussion with some teachers providing written observations. Reference to the rubric to situate this formative feedback was commented on by several teachers citing its use to direct conversations and focus observations in specific lessons. A representative comment is reproduced below:

[the rubric] helped to focus on which competencies the pre-service teacher was being assessed against. Helped direct focus onto areas needed to be worked on.

Whilst a number of colleague teachers commented on the use of the rubric as a starting point for supportive and focused feedback, both colleague teachers and university supervisors found the rubric very useful in highlighting specific areas for further development for students at risk of failing the practicum. One colleague teacher commented on being able to give feedback that was "less personal" which was "very helpful if student is weak". Another postulated that the rubric was "maybe more so [helpful] if pre-service teacher was not meeting expectations". Using the rubric was also seen to assist in pointing out areas of strength.

Although most responding colleague teachers reported using the rubric for both formative and summative assessment, a small number used it only for the final assessment, nevertheless finding it useful. Clearly, the rubric is a seen as a valuable tool for assessment by the majority of teachers. It may be, however, that there does need to be some induction around its use for new colleague teachers or colleague teachers in some specialisations such as LOTE.

After having used the rubric for the practicum, all responding colleague teachers found that the indicators were appropriate for the pre-service teacher's level, although there were some qualifying comments about school factors influencing opportunity (most notably indicators concerned with using ICT and performing assessment). A specific example was one early childhood teacher who mentioned that ICT was 'not used much' so believed that this indicator was, therefore, not applicable to this grade level. Time was also an issue mentioned by two colleague teachers – time constraints in busy school programs sometimes preventing an opportunity to meet all criteria.

In so far as providing the developmental sequence on a single rubric, all the colleague teachers could foresee their pre-service teachers attaining the next level on the assessment rubric in their subsequent practicum. It was noted by several colleague teachers that the opportunity for the pre-service teacher to experience each of the indicators has to occur before they can be considered competent in that area. Therefore, having the assessment rubric early and the opportunity to clarify expectations was seen as a benefit.

Apart from the one colleague teacher in the LOTE area, no colleague teachers made specific recommendations with respect to refining the rubric. Although acknowledging that some indicators may be insufficiently addressed due to school factors (such as the use of ICT in the infant class), and that there needed to be some professional judgement, colleague teachers strongly supported the use of the rubric in its current form. In terms of specific indicators, teachers believed that they were appropriate, and many indicated that the stronger pre-service teachers would be able to achieve indicators at the higher level. One colleague teacher specifically mentioned how the rubric also provided "a good roadmap" for pre-service teachers.

There were two specific suggestions made by colleague teachers with respect to extending the use of the rubric. The first was to investigate the possibility that pre-service teachers use the rubric in a more developmental sense. It was envisaged that the pre-service teacher could keep a copy of the rubric and mark off each of the indicators in successive practicum placements. This rubric 'in progress' would then be available for each new colleague teacher to see, hence giving an indication of areas of strength and areas where the pre-service teacher may need some extra experience and support. Similarly, where a student was repeating a practicum, it would be very clear to their new colleague teachers in which areas they needed to develop.

A second suggestion by the colleague teachers was to use the rubric to enable the differentiation between a satisfactory performance in the practicum and a performance that was at a higher level. The colleague teachers at the feedback session spent some time discussing the possibility of formally recognising such high performing students and noted that the inclusion of the fifth level in the assessment rubric could assist in this acknowledgement.

Pre-service Teacher Evaluation of the Rubric

The return rate of surveys from pre-service teachers was quite low (12 out of 30, representing 40%). Nevertheless, the responses to the two questions relating to the rubric were reasonably consistent (Table 2). Pre-service teachers were firstly asked to comment on the extent of use of the assessment rubric by their colleague teachers. All except two of the pre-service teachers indicated that their colleague teachers referred to the rubric during the practicum (one of these was unsure). Just one pre-service teacher reported this only occurred during the final assessment. The remainder reported their colleague teachers referred to it either once or twice – or several times during the practicum (76%). This tallied with colleague teacher data who reported they had used the rubric to initiate feedback or to determine appropriate experiences for the pre-service teacher. This was also supported by the accounts of the university supervisors who saw evidence in most schools of the rubric being used to guide performance expectations, and who received direct questions concerning the indicators from both colleague teachers and pre-service teachers.

Table 2: Pre-service teachers' feedback on the assessment rubric

| 1. Pre-service teachers' assessment of colleague teachers use of the rubric | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

My teacher referred to the rubric: |

Not at all |

Unsure |

Only for final assessment |

Once or twice through the practicum |

Several times through the practicum |

|||

8% (1) |

8% (1) |

8% (1) |

51% (6) |

25% (3) |

||||

2. Pre-service teachers' assessment of colleague teachers use of the rubric |

||||||||

The rubric helped to clarify expectations: |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly agree |

||||

0 |

18% (2) |

55% (6) |

27% (3) |

|||||

It was also important to determine whether the indicators in the rubric were useful to the pre-service teachers in clarifying expectations of the practicum. An overwhelming 82% agreed to this statement (with 27% strongly agreeing), the remainder being neutral.

A University Perspective on the Rubric

Use of standards-based rubrics for field based assessment is gaining widespread acceptance across the tertiary sector (Kleinhenz & Ingvarson, 2004; Poikela, 2004; Tang & Chow, 2006; Tang, Cheng & So, 2006). The use of criteria not only allows assessment to be more focused and equitable to students (Poikela, 2004), it clarifies expectations for all stakeholders, ensures allocation of appropriate responsibilities, and prompts useful feedback (Brown 2007). Importantly, developmental rubrics or similar instruments provide a framework for pre-service teachers to self monitor and self assess.

The findings of Tang and Chow (2006) are remarkably similar to what has been found in Tasmania. In looking at how the Hong Kong assessment framework was used in field experiences to support communication of feedback to pre-service teachers, they found that the clarification of assessment criteria was particularly important in promoting learning-oriented assessment. The potential for rubrics or frameworks to focus feedback from colleague teachers is particularly important. Delivery of focussed feedback – supportive in nature and sensitively delivered – has been identified as being important to support assessment for learning principles (Caires & Almeida, 2005) and to promote the development of the pre-service teacher's pedagogy (Jordan, Phillips & Brown, 2004).

Whilst the rubric has been successful in clarifying expectations and articulating sequential development of pre-service teachers, it would be remiss not to comment on the limitations of these findings. Despite the reference to the rubric on all assessment proformas, and the additional documentation and support around this project, there remained one teacher (who responded to our survey) who did not know of the rubric through the practicum. Although once alerted it was seen to be useful, the question of how many teachers not involved in the evaluation were unaware of the rubric must be asked. This issue has also been raised elsewhere. Brett (2006) identified that some teachers are placed in a supervisory position without being aware of the requirements and Ganser (2002) discussed how many, without opportunity to participate in organised induction programs, find the role somewhat confusing.

With increasing pressures on teachers in schools, reducing complexity of assessment of pre-service teachers, whilst maintaining appropriate collaboration, is vital. It also needs to be recognised that despite goodwill on all sides, and, in the case of this study, incentives to attend, many teachers are unable to participate in briefings or inductions. Clear, user-friendly documentation regarding practicum is, therefore, essential if the goals of the Government report (in terms of clarifying expectations) are to be met. Although the majority of colleague teachers found the rubric accessible and easy to use, this study indicated that it remained important to alert colleague teachers to the appropriate indicators on the rubric prior to, or early in, the practicum placement, particularly if they are new to the role or in specialist areas such as LOTE. Colleague teachers, who did attend the induction, strongly supported continuation of this event. However, direct communication between the university supervisor and the colleague teacher would appear to be the most effective method of ensuring important information is relayed, and opportunities for clarification can occur.

Conclusion

In a pre-service teaching program, Professional Experience brings together the different disciplines of Education into a real-world setting. Helping pre-service teachers see theory in practice and begin to put theory into practice requires a close and explicit linkage between the coursework and practicum. A shared discourse accessible to pre-service teachers, field-based colleague teachers and university lecturers is an essential element in this process.

Indications from both the quantitative and qualitative data collected in this evaluation were that the rubric was positively received by all stakeholder groups (pre-service teachers, colleague teachers and academic supervisors). The continued use of the rubric as an assessment tool was unanimously supported. The indicators at each level of achievement were seen as appropriate and no adjustments were recommended. In particular, the rubric was identified as being successful in: clarifying expectations of student performance (for both colleague teacher and pre-service teacher); ascribing appropriate learning experiences in the field setting for pre-service teachers at each developmental stage; providing a starting point for supportive and focussed feedback; assisting the support of students at risk of failure; and, providing for students to be stretched to meet 'aspirational' outcomes, therefore, giving an opportunity for high achieving students to be recognised.

It is recognised that this is a time of significant activity in the area of teacher professional standards and registration requirements (Darling-Hammond 2001; Kleinhenz & Ingvarson, 2004; Tang, Cheng & So, 2006). Therefore, the likelihood of Federal or State agendas altering indicators appropriate for pre-service and graduating teachers is high. Nevertheless, whilst the indicators in the rubric may change, the format - in particular, the explicit indicators and the developmental sequence - will remain effective in terms of creating a shared discourse amongst stakeholders, clarifying expectations, assisting in moderation of experiences and assessment, and promoting opportunities for self assessment to direct professional learning.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the work of Kate Shipway in the Professional Experience partnership research and in facilitating the Partners in Professional Practice Working Group from which the larger project was conceived. She would also like to acknowledge Lynda Kidd who was the research assistant on the project.

References

Arnold, J.; Loan-Clark, J.; Harrington, A. & Hart, C. (1999). Students' perceptions of competence development in undergraduate business related degrees. Studies in Higher Education 24, 43-59.

Australian Teaching Council. (1996). National Competency Framework for Beginning Teachers developed by the National Project on the Quality of Teaching and Learning, ATC.

Boud, D. (1999). Avoiding the traps: seeking good practice in the use of self-assessment and reflection in professional courses. Social Work Education 18(2), 121-132.

Brett, C. (2006). Assisting your pre-service teacher to be successful during field experiences. Strategies 19(4), 29-32.

Brown, N. (2006). Professional Experience – Development of an assessment rubric. Proceedings of the Australian Teacher Education Association Conference, Fremantle, July 2006. [CD Rom]

Brown, N. (2007). Development of a Professional Experience Rubric. From the REAP International Online Conference on Assessment Design for Learner Responsibility, 29th-31st May, 2007. Available at http://ewds.strath.ac.uk/REAP07

Brown, N. & Shipway, K. (2006). Partnerships in Professional Experience: A collaborative model. In Bunker, A. & Vardi, I. Critical visions: thinking, learning and researching in higher education : proceedings of the 2006 annual international conference of the Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia Inc (HERDSA), 9-13 July 2006, The University of Western Australia.

Caires, S. & Almeida, L.S. (2005). Teaching practice in Initial Teacher Education: its impact on student teachers' professional skills and development. Journal of Education for Teaching 31(2), 111-120.

Connor, K. & Killmer, N. (1995). Evaluating of cooperating teacher effectiveness. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Educational Research Association, Chicago.

Creswell, J.W. (2003). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Darling-Hammond, L. (2001). Standard setting in teaching: Changes to licensing, certification and assessment. In Richardson, V. (Ed), Handbook of research on teaching. Washington: American Educational Research Association.

Darling-Hammond, L. & Baratz-Snowden, J. (2005). A good teacher in every classroom: Preparing the Highly Qualified Teachers Our Children Deserve. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Department of Education, Tasmania (2005). Essential Learnings for All Inclusive Practice Professional Teaching standards. Retrieved April, 10, 2006 from http://www.ltag.education.tas.gov.au/focus/inclusiveprac/ELforalldocs/book2.pdf

Haigh, M. & Tuck, B. (1999). Assessing student teachers' performance in practicum. Paper presented at Australian Association for Research in Education. New South Wales Institute of Teachers, 2005, Professional Teaching Standards. Retrieved March 10, 2006, from http://www.nswteachers.nsw.edu.au/IgnitionSuite/uploads/docs/18pp%20PTSF%20book%20v6.pdf

Eyers, V. (2005). Guidelines for quality in the practicum. ANU Canberra: National Institute for Quality Teaching and School Leadership.

Ganser, T. (2002). How teachers compare the roles for cooperating teacher and mentor. The Educational Forum, 66(4), 380-386.

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education & Vocational Training, (2007). Top of the Class. Commonwealth Government of Australia, Canberra.

Jordan, P.; Phillips, M. & Brown, E. (2004). We train teachers: why not supervisors and mentors? Physical Educator, 61(4), 219-221.

Kleinhenz, E. & Ingvarson, L. (2004). Teacher accountability in Australia: current policies and practices and their relation to the improvement of teaching and learning. Research Papers in Education 19(1), 31-49.

Lizzio, A. & Watson, K. (2004). Action Learning in Higher Education: an investigation of its potential to develop professional capability. Studies in Higher Education 29(4), 469-488.

Miles. M.B. & Huberman, A.M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Ortlipp, M. (2003). The Risk of Voice in Practicum Assessment. Asia-pacific Journal of Teacher Education 31(3), 225-237.

Patton, M.O. (1990). Qualitative research and Evaluation Methods. Newbury Par, CA: Sage

Poikela, E. (2004).Developing criteria for knowing and learning at work: towards context-based assessment. The Journal of Workplace Learning 16(5), 267-274.

Schon, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Tang, S.Y.F.; Cheng, M.M.H. & So, W.W.M. (2006). Supporting student teachers' professional learning with standards-referenced assessment. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 34 (2), 223-244.

Tang, S.Y.F. & Chow, A.W.K. (2006). Communicating feedback in teaching practice supervision in a learning-oriented field experience assessment framework. Teaching and Teacher Education 23(7), 1066-1085.

Thomson, P. (2000). The Sorcery of Apprenticeships and New/Old Brooms: thinking about theory, practice, "the practicum" and change. Teaching Education 11(1), 67-74.

Turnbull, M. (2003). Student Teacher Professional Agency in the Practicum. ACE Papers: Working Papers from the Auckland College of Education, 1-17.

In the UTAS Bachelor of Teaching program, pre-service teachers complete four practicum placements, totalling 90 days. These placements are structured to assist development of teaching practice – from initial introduction/orientation to the profession through to the complexity of an internship.

Footnotes

1 There are four pre-service teaching programs in the Faculty of Education at UTAS. At the time of writing, each used a different assessment protocol.